It is important to remember that the Cultural System which we are looking at is merely one of many. Some will be very close while others will have very little to do with it. That is important because we are looking at the Cultural System which reflects on our time specifically and with each day the changes will pile up so that eventually a new Cultural System will be inevitable. What we are looking at the specific moment is how a generation born between the beginning of World War II in Europe and eventually collapsing in the 1960s wishes to continue even though they are numbers are increasingly depleted. Once this is determined to be the fixing point in the present, we can then see how each phase leads to another new one. However, we have not determined what causes new phases to occur.

We had some inclination as to its effect in the Modern period of time, because it was clear that the resources and thought patterns of the Cultural System were not sufficient to maintain control over the global policies. And those global policies seemed necessary to control the economics, politics, and cultural vectors. This led us to speculate that the introduction of atomic weapons changed the way that political alliances were cemented and the mechanisms to continue those alliances. However, this did not yield a complete result, and it meant that we had to examine additional phases to see where the Cultural System broke down.

It should be obvious that one aspect of the Cultural System breaking down is that the top level wishes to do an action or series of actions, but the bottom of society disagrees on a fundamental level. For example, the Modern period wanted to control the production and distribution of resources for the entire society. However, to do this required a series of inventions, the most obvious is the introduction of atomic weapons but the aircraft carrier, the introduction of dwellings built in the same manner as military bases, and other forms of nationalizing the production made it impossible to do so in a Modern fashion. Essentially creating a Modern system required Postmodern ideas that broke the Modern system.

The question is whether this is unusual or is a pattern that this Cultural System employs regularly?

But this means since we cannot perform experiments that we must peer backward to another system and why it collapsed. Before the Modern could introduce a world war another system had to do so. We can prove directly that this new Cultural System was different from the Modern and therefore it should produce a similar collapse.

This means that before the Postmodern came the Modern, and before the Modern came another Cultural System. Because there are many names for the premodern system, this book will use the Neoclassical as the umbrella term to describe the late 1800s and early 20th-century pattern. And we can see that there is a breakpoint at the beginning of the First World War which mirrored the breakpoint in the Second World War. In both cases, the drive at the top of the hierarchy is to control the production of goods and services in a framework that is conducive to the Cultural System.

But that Cultural System did not see that the requirements of controlling production ultimately did not work. This is because they had an idea of how production could be controlled and how it could be administered. In the Modern, this was under the control of a monetary system that required a macroeconomic structure. But in the Neoclassical the idea that there was such a thing as a macroeconomic structure was abhorrent. The doctrine of the time in the capitalist countries was that “the market” could control the entire structure and be doctrine in the USSR was that the top level should control everything, and the doctrine in the states that were controlled by a monarchy was that the monarch could control everything to achieve the ends that the top level wanted.

But this is theoretical, and we need to zero in on specifics.

The Difference between Modern and Neoclassical

First, we must discuss what is different between the Modern and the Neoclassical. Then we can expand the definition to different activities. Finally, we can see how the Neoclassical order came to be controlled by the very top while the bottom was controlled by different forces which would eventually be called the Modern. Then we can look to the past to see where the Neoclassical system took hold and why it remained in power despite various challenges. At that point, we can point to a marker that changed the system to the Neoclassical from what came before it.

So, by the end of this section, we can point to the moment when the Neoclassical order lost control of the political, cultural, and economic forces and at the moment when the Neoclassical order took charge of those same forces at the other end.

What distinguished the Neoclassical order from the Modern order? Since there are a variety of disciplines the answer is multi-variant, but since we are looking at when the top of the political and economic system is Neoclassical while the rest of the Cultural System has started to make changes, that means that we are looking for the moment when a marker is at its most extreme. This means that we have to look for the moment when the Neoclassical elite charges into a situation that the majority of society regards as stupid, insane, or at least illogical. That moment is rather clear: the decision to go to a European-wide conflict, leader called World War I but even at the time called The Great War.

Why is World War I such an anomaly? Consider that during the long 19th century there were only two wars that came close to matching World War I: the Crimean War and the American Civil War. All other conflicts had been mere skirmishes from the collapse of Napoleon the First. This is a record for the European continent up until this point in time, and with only two exceptions it is easy to think that there has been piece since the Congress of Vienna ordered a new framework. In addition, since the American Civil War was not on the European continent, many writers did not count this war as “European” in the same way they did not count the wave of revolutions that took place in the Americas between 1791 and 1822:

In essence, this was counted as part of the French Revolution in that a new wave of independence had taken over the New World. But this meant that there were several wars in the 19th century that were discounted. But when looked at clearly, the idea that there was a long period of peace is not quite so clear-cut.

But does this matter to the present Cultural System?

This is why mathematically determining a marker is important: one needs to know when the Cultural System that you are looking at begins, peaks, and ends to understand its significance. With the Modern era beginning at some point around 1890, it is clear that the Modernist project is not responsible for a long era of peace. Similarly, the Neoclassical Should be examined as to when it began. But to do this requires a marker as to when the Neoclassical ended.

Fortunately, the outbreak of World War I has the advantage of being a signature moment because the Neoclassical era worked to have small wars that ended relatively quickly even if there was a longer-term objective in view. The most obvious example was the wars to unify all of Germany: the Second Schleswig War which was between Prussia and Denmark and in slightly more than eight months in 1864, a war between Prussia and Austria which lasted only a little over a month in 1866, and finally a war with France which was completed in slightly over six months. In short, the amount of bloodshed to form the German Empire was only more than a year.

The reason that the Neoclassical usually fought such short wars was understandable given the fragile nature in which peace found itself. Remember, this was before the total warfare of World War I and World War II, and miles from the atomic warfare after 1945 - at this point war was a string of battles, not the mass mobilization along several fronts. The nations of Europe did not want long drawn-out wars because they would be too costly to sustain.

It is not that warfare is an aberration, but a consequence of deliberate choices made by both the elites of a political system and often times the constituent parts of the civilian members. In other words:

States may fight - indeed as often as not they do fight - not over any specific issue such as might otherwise have been resolved by peaceful means, but in order to acquire, to enhance, or to preserve their capacity to function as independent actors in the international system at all. “The stakes of war,” as Raymond Aron has reminded us, “are the existence, the creation, or the elimination of States.”i

The entire reason, according to this logic, is to make larger decisions on the nature of states.

In this book, it is proposed that the beginnings of a Cultural System form when there are discrepancies between the then Cultural System and observed events or reasoning. If the system continues to form, it finds internal consistencies in its logic, and at some point, it begins to have consequences when the old Cultural System cannot resolve the inconsistencies. Because there are at least two mechanisms of the Cultural System, one from the ground up and the other from the top down, there is often a collision between the old Cultural System and the new Cultural System. At the end of a Cultural System, the top-down elites are working primarily in the old Cultural System and they do not understand why those who are younger do not see things the way the top see them.

In the case of the Neoclassical, the problem was that the old system could result in small conflicts but had difficulty with larger conflicts. This meant that the original idea of going to war in 1914 was to resolve small disputes. Unfortunately, this went out of control and we have a marker at the ending of the first battle of the Marne.

Why the First Battle of the Marne was a Turning Point

Just before the beginning of what would be called World War I, there was a consensus that it would be a short war and then negotiations would take place delimiting what had happened and small changes to how the European world would run afterwards. But there were problems on both sides. One is that while population pyramids were not formally established, the idea was known and certain large powers were going to lose ground in the coming years. For example, all major powers past manpower acts to ensure that they would have enough manpower to draw forces from in the case of an impending war.i Since at least 1905 there was pressure in many of the capitals of Europe that a war might calm and there were increasing attempts to stop such a war on the other hand groups who wanted a war pushed for a war at the appropriate time. Again the idea of a Late Stage was not established at all. There was the notion that advancements in technology such as subways and electrification were transforming the way that a city should be managed. But a war intervened and changed the nature of what could be done.

Thus, on July 23, 1914, the monarchy of Austria-Hungary transmitted an ultimatum to Serbia which sides knew was unacceptable.ii The question that has bedeviled historians is whether or not the July 23 ultimatum would boil over to a more general war between the two power blocs of Europe at the time: the Central Powers and the Entente. But both alliances were kept secret as to how far and under what circumstances each of the alliances would come to the aid of others in their alliance; specifically, would guarantee that a lesser power be backed by the same force as a direct assault? This volume does not answer this question because the question of the book is different. It is asking where the war that broke out becomes a globalized war as opposed to a skirmish that could be resolved after a small amount of fighting and then negotiating the results?

This is a different question than “Would the major powers go to war?” because almost all of the military commanders were thinking of a war similar to the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1. This was a fairly short war and while it was bloody, with estimates of around 184,000 military fatalities and another 250,000 civilian casualties, this did not bother the military generals at the time. And pales in comparison with the First World War’s estimates of 9 million military dead and an additional 8 million civilian fatalities. So the question is when did markers suggest that the First World War become the First World War? That is to say, we do not want to assign blame but are looking for the marker that tells us that the Neoclassical-trained civilian and military leaders had gone beyond what the Neoclassical order could manage.

This means that the invasion of Serbia by Austro-Hungarian forces was not the moment where casualties would pile up beyond recognition. Even the German advancement through Belgium was not that point either, because it was certainly possible that the Germans could win a decisive victory and then negotiate for favorable terms. And it must be stressed that a marker merely means a signal, not a decision: we are looking for the marker of forces.

This means that the population pyramid had a weight behind it, but it itself was not the moment where civilian and military leaders on both sides had committed their troops to a total victory.

Fortunately, there is such a marker and it happened soon after the war was started: it was the end of the first battle of the Marne.

When the topic of World War I is rehashed by historians, there is a great deal of argument over whether the war should have happened at all.iii It might seem strange that this book has picked a specific military event as the breakpoint for the elite finally determining that the Neoclassical age had ended, but this question is not important to this work. This is because the breakpoint would occur at some instant when the elites of the great powers reached an end that was outside of the capacity that the Neoclassical age could not achieve. However, many of the historians who argue that the war should not have happened argue from the point of individuals who saw that the Modern world was capable of more destruction than Neoclassical age could repair. The problem with this argument is that we are not talking about the imaginings of people who were not part of the halls of power but taking a look at individual people, largely men, who saw things in a different manner than did people who pursued industry, commerce, and the arts of peace.

But before 1914, there were plans to wage a short, but exceeding bloody war. Of course, students will know the Schieffelin Plan on the German side, but Nicholas Lambert’s position is that Britain to have a plan, but it was economic, not military. The idea in Great Britain was that because of their control over the levers of economic power including currency, they could ameliorate the damage to their own economy and accentuate the damage to Germany with collateral damage to the rest of the world’s economic output. Because if no one had money then the economy of most countries, which depended on exports, would collapse in a manner similar to the “Long Depression.”iv The Problem was that the scale of the economic catastrophe was far larger than the UK government’s projections.v This means that there is the possibility that the United Kingdom envisioned a short war but with different consequences. Remember, while up wars were short, the Neoclassical age felt that conflicts were generational but involved economic conflict rather than military conflict. This means that the factories would continue to be built because the destruction of a particular war would be short in the scale of the conflict:

Widespread expectation of imminent war between the European powers during the last week of July 1914 generated a financial crisis of unparalleled severity. Though such a shock to the global economic system had been widely anticipated, not least by the Desart Committee, everyone was surprised by the scale of the panic, the speed with which global confidence collapsed, and the magnitude of financial devastation. Historians of the First World War have scrutinized the intricate diplomatic maneuvers in the weeks leading up to hostilities, as well as the political turmoil attending and generated by the decisions to set prewar military preparations…vi

This idea is antithetical to the Modern sense of warfare but that is because our framework is the three global wars: World War I, World War II, and the Cold War. Only the Cold War is in the framework of what politicians would consider a global competition, the difference is that the Cold War could heat up to a “hot war” at any given time, something that the Neoclassical governments were not worried about because they had not seen this sort of devastation with only two exceptions: the American Civil War and the Crimean War, of which were out of the Western European theater and therefore not entirely relevant. Or so the Neoclassical age thought: there was war between the major powers, and there was devastation that meant very little to them.

This means that the Modernity that we see in the mobilization of 1914 and the tremendous advancements since the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 looked very different from the perspective of a military class that saw them as advancements that could extend the reach of their state. Consider that the truck was to them a means of supplying men and evacuating wounded more efficiently than by horse-drawn carriage. Similarly, when the rise of airplanes and then of the Air Force came in, the military class saw it as a way of dominating the air rather than changing the relationship. When the tank was brought into being there was confusion about what it would do to entrenched lines. In other words, it is not the individual pieces but the overwhelming idea that the nature of war has changed. Even if there had been no war at all, people like the Kaiser with his entourage would have missed the point of a world that had fundamentally changed in people in it who thought differently. What this means for this book is that the moment that Modernity had dawned would come eventually even though it may have dramatically altered what the Modern was to be. Already the Neoclassical had overrun its boundaries: the war needed industrial Modern equipment And therefore the Modern was already coming to be. The warfare is no longer the Battle of Königgrätz. The scale is larger.

Consider that wars had recently been fought in the Balkans with the mean takeaway that the Ottoman Empire was collapsing. In the capitals of Europe, this meant that there was a vacuum, and a vacuum needed to be filled. This is because in the war of 1914, one point of view was necessary, but in another point of view it was ordained. It does not matter that the people in the war were unnecessary thought because they were not the people upon whose judgment the war actually came.

The Balkan Wars of 1912/13 and their outcomes have shaped much of the military and political thinking of the Balkan elites during the last century. At the same time, these wars were intimations of what was to become the bloodiest, most violent century in Europe’s and indeed humankind’s history. Wars often lead to other wars. Yet this process of contagion happened in a particularly gruesome manner during the twentieth century. In Europe, the Balkan Wars marked the beginning of the twentieth century’s history of warfare.vii

The elites in charge of military power had seen in 1913 just what devastation could be inflicted by the units they commanded. That there was going to be devastation was clear to the militaries of the major powers. Even if the events of the summer of 1914 did not lead to conflict, it is the structure of society and the artifacts that it produced that is this book’s major point. If it had not been at the end of an offensive battle, it would have had some other point because the Modern was reducing a myriad of tools which would eventually disrupt the Neoclassical age.

The story that was common in Western Europe in the 1920s was that Germany had started the war and prosecuted it with righteous fury in order to have their place in the sun. but a case can be equally made that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was trying to fill the space left by Turkey Serbia was attempting to secure a space has the leader of the Slavic people there and the Austro-Hungarians and the Serbians were trying to establish dominance over the Balkan region. In this view, Bismarck’s feeling that the peace of Europe was resting on the referees of Europe, meeting the Balkans, was not a slipshod remark but the fact that conflict in the balls was brutal and could not be managed way to the conflict on the Western front was. This had been true since the 1860s, the difference being that for much of this time, Bismarck was in control of the outlets in the Balkans.viii Those who came after him were not and did not understand that suppressing war was a vital step towards maintaining Germany as a great power.

Thus, while it seems likely that a war would have broken out, and more importantly a Neoclassical command would lead to an overreach, it is not necessary nor is it essential that a war would have been the main culprit. After all the Neoclassical age was confirmed by connecting the Americas to Europe and the rest of the old world. The event was not the trigger, but a confirmation that a new age had begun. An example of this bias to the blindness of the 19th century was found in the meetings of the German high command often with the Kaiser heading the meeting. Consider:

My close relations with the army are a matter of common knowledge. In this direction I conformed to the tradition of my family. Prussia's kings did not chase cosmopolitan mirages, but realized that the welfare of their land could only be assured by means of a real power protecting industry and commerce. If, in a number of utterances, I admonished my people to "keep their powder dry" and "their swords sharp," the warning was addressed alike to foe and friend. I wished our foes to pause and think a long time before they dared to engage with us. I wished to cultivate a manly spirit in the German people; I wished to make sure that, when the hour struck for us to defend the fruits of our industry against an enemy's lust for conquest, it should find a strong race.ix

While this was written after the war and must therefore be supported by other texts, it is pretty clear that the view from the top of Germany was not of “peace at any price.” This is largely because the Postmodern regards war as a pure unadulterated evil. And with nuclear weapons and other sorts of strategies employed by the states, there is no doubt that this is entirely reasonable, indeed the almost sane position. Except if you are the leader of one of the most militarized states on the planet.

We will take two more examples to enunciate the fact that what is reasonable over a century later is madness when one is at the top of the greatest army regime in the world:

In view of its proud duty as an educator and leader of the nation in arms, the officer corps occupied a particularly important position in the German Empire. The method of replacement, which, by the adoption of the officers' vote, had been lodged in the hands of the various bodies of officers themselves, guaranteed the needed homogeneity. Harmful outcroppings of the idea of caste were merely sporadic; wherever they made themselves felt they were instantly rooted out.x

That is if there were any officers who were disloyal they would be “instantly routed out.” This means that opinions such as bank officers or shipping magnates would be dismissed because the “loyal officers” would be in unison in supporting their Kaiser. And finally:

During the next few days, there were constant reports that the Socialists in Berlin were planning trouble and that the Chancellor was growing steadily more nervous. The report given by Drews to the Government, after his return from Spa, had not failed to cause an impression; the gentlemen wished to get rid of me, to be sure, but for the time being, they were afraid of the consequences.

Their point of view was as obscure as their conduct. They acted as if they did not want a republic, yet failed completely to realize that their course was bound to lead straight to a republic. Many, in fact, explained the actions of the Government by maintaining that the creation of a republic was the very end that its members had in view; plenty of people drew the conclusion, from the puzzling conduct of the Chancellor toward me, that he was working to eliminate me in order to become himself President of the German Republic, after being, in the interim, the administrator of the Empire.

This shows that at the top, the opinion held was that if everyone had joined together in support of the Kaiser the end would be a tremendous victory.

But the military was the only side of the war. England started the war with a short victory condition based on its control of the currency and the fundamental value of currency which at that time was gold. Unfortunately, while they could control the currency they could not determine absolutely where the damage was inspected, most specifically the amount of damage that the United States would take. Therefore, bit by bit, they allowed imports and exports of various different commodities particularly energy in the form of coal to be traded without reference to the currency exchange. In other words, they allowed people to trade without consequence. The Germans then in 1914 produced the “Septemberprogramm" which was the post-war plan that the German Empire would like to see.xi It was penned by the Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg. Being now it is like listening to the deluded ravings of a lunatic, because after all we live in that future where the German Empire ceased to be and the Kaiser fled to the Netherlands. It is important to remember that the Chancellor acted for the Kaiser and was in no way responsible to the elected government. In essence, the Chancellor was the Kaiser’s representative in the Reichstag and thus it is better to think of the Kaiser as a member of a political party that had other members with the same objectives. The September program stated that a small chunk of France should secede to German control, that Belgium should be annexed either as a territory or a vassal state, but most importantly that the entire zone of “MittelEuropa” which included Germany, Austria, France, Belgium, Denmark, and Poland at least and perhaps Italy as well, would the under German control and “it must stabilize Germany’s economic predominance in central Europe.” This means that the entire war from the Kaiser parties’ standpoint was about economic control far more than military control and the specific absence of Great Britain as a power on the Continent was keyed.

However, it was the German army that would have control over any civilian apparatus. Which is to say the Schlieffen Plan was the mechanism to deliver the state of Europe as a German-dominated economic entity. One can see how the Neoclassical had been wrapped up and tossed overboard from the beginning, but there was new logical system to replace neoclassicism.

But what was the exact problem?

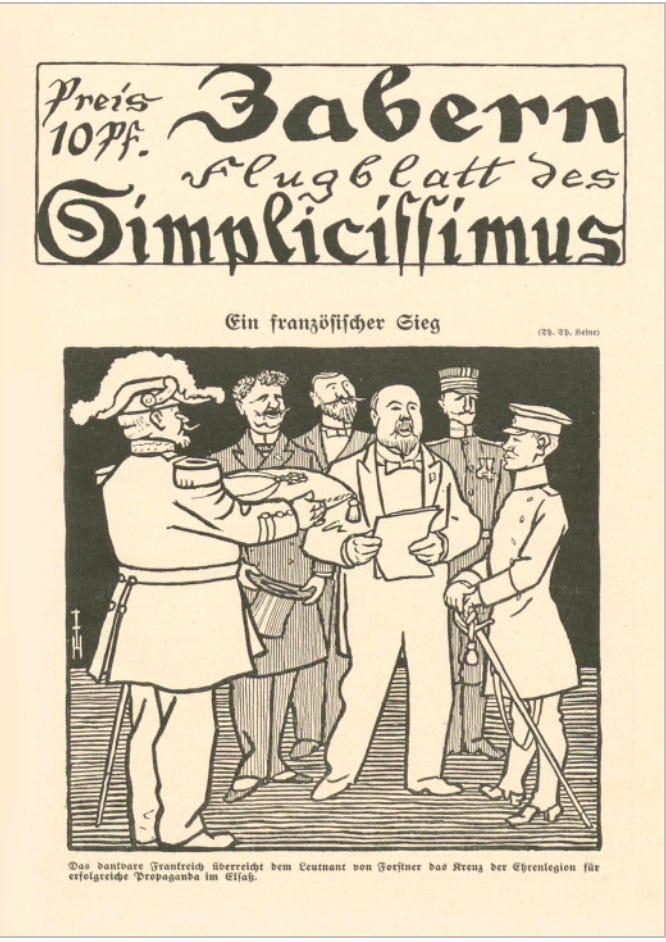

The army showed that militarism was in the bones of the military as the Zabern (Saverne) Affaire showed. If you are familiar with the town of Saverne, realize that was contained within Germany and have heard of the settlement of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71. The people wanted to run their own affairs, but two military battalions of the German Army were trained to regard honor as one of the benefits that the German Army should maintain. A second lieutenant, Günter Freiherr von Forstner, insulted the inhabitants and told his men to use force if attacked by the civilians and they also warned about aggressive language from French Agents. This was the language of a young man who wanted to keep under discipline is subordinates and worried of their going off to the French Foreign Legion. It is not a tirade against imperialism but be worried about his soldiers being poached. The young men would die in the upcoming great war. This is not to say that militarism was the cause of the war but when militarism was invoked militarism expanded the discussion beyond its original endpoint.

Nor is it a prescription for militarism among the populace but only among the military. And then from the top, it seemed that the military needed a firm hand. However, the second lieutenant went far beyond his mandate, and when the Elsässer (that is the Alsatian), and the Zaberner Anzeiger (the Gazette) reported this, the response the military was to issue a token punishment to the second lieutenant, which was not reported, and publicly arrested 10 men for reporting the comments to the press. This caused a firestorm not only in the town but across other towns complaining that the Army was against civilians. Daily things escalated on the 26 of November when the garrison drove a number of civilians into a side street and arrested several with no particular charge.

The result was that it was bullying by the Army that was the tension across several towns. In a larger sense, it was a contest between the Army, and its sense of discipline and order, against the civilians, who wanted civility. And the Kaiser showed little interest in the tensions between the Army and the civilian leaders, and when they did old a meeting he only invited the military for their point of view. This told even the junior officers that defending the honor was more important than respecting the citizens. And on 2 December Forstner made a second blunder, knocking over a civilian for not saluting the military. This was because the civilians could not stand. In the military tribunal, a was sentenced to 43 days of arrest but this was reversed on appeal.

However, this would have blown over it and were not for a no-confidence vote in the Reichstag. The problem at a high level was the same as at the low level: while the civilians wanted the resignation of Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, only the Kaiser could remove him. In other words, the Chancellor was not a Prime Minister who served at the will of representatives but at the sole will of the Kaiser. After the arrays by the representatives to thwart the Chancellor’s budget the Kaiser then realized that some accommodation had to be worked out and that led to a law which said the civilian authorities needed to request the military.

At a higher level, this shows that militarism was not at the forefront of the civilian population of Germany, but it was core to the idea of the German Army. And the Army took its cues from the Kaiser who wanted discipline and unity from the Army and militarism was part of this form of organization. This did well in the Neoclassical age when the armies were smaller, the protests were weaker, and the ideas of socialism, democracy, and civilian rule were less advanced and not as well organized. But as the Modern age grew in force it made the Army larger, and the Chancellor more dependent on the Kaiser, and on the other end, it made political parties stronger, more organized, and more unified. This means that what had worked in the 19th century was less useful now. it was not imperialism but Modernization. However, the leaders did not understand that Modernization applied both to the lower-level individuals and also to the leaders. This means that one does not go on vacation when a turbulent intervention is in progress.

The problem is that the incident continued in other forms. a good example is in the satiric novel Der Untertan (The Underling or The Subject) by Heinrich Mann. This controversial novel made the protagonist, Diederich Hessling, a slavish, or better to be said a Germanophile, worshiper of the Kaiser. Important is the disparity between words and actions: his words say that he is an obedient servant, but his actions are to be duplicitous if he sees an advantage. He wears the stripes of a coward but realizes that the powerful want an intermediary to distance themselves from the actions that there was created:

Diederich Heßling war ein weiches Kind, das am liebsten träumte, sich vor

allem fürchtete und viel an den Ohren litt. Ungern verließ er im Winter

die warme Stube, im Sommer den engen Garten, der nach den Lumpen der

Papierfabrik roch und über dessen Goldregen- und Fliederbäumen das

hölzerne Fachwerk der alten Häuser stand. Wenn Diederich vom Märchenbuch,

dem geliebten Märchenbuch, aufsah, erschrak er manchmal sehr. Neben ihm

auf der Bank hatte ganz deutlich eine Kröte gesessen, halb so groß wie er

selbst! Oder an der Mauer dort drüben stak bis zum Bauch in der Erde ein

Gnom und schielte her!xii

In other words, he was a satire of the organization that the Kaiser wanted: both scared and violent, saying he would do his duty but always looking to cheat, if you will a person who would smile anyone’s face and stab him in the back. Again, this worked when the stakes were domestic or when a war could be completed with one decisive victory and then terms were to be established with the victor dictating the treaty in that there were limits to how long cheating could go on because there was an account to be made. Even the Chancellor would only tell lies about someone for so long, for example, the Kulturkampf from 1871-8 against the Pope and ethnic minorities. Remember this is what the Neoclassical regime established: short wars over specific disputes, unlike the American Civil War and the Crimean War combined with fearful struggles against “the other” who was hiding out in the same sight.

Now we can this sect what was Neoclassical and what was Modern. The Modern is bound in even the Kaiser’s memoirs in that production of the news would help the cause. But it is with the Neoclassical that the will of the Empire, that is the will of the people to stay in line with the Kaiser, would make it so that Germany would be triumphant. And with the short wars that had built Germany from Prussia, this had been the case. The problem is that there was a question, a question not even asked by the Kaiser: “How long would this last?” In fact, none of the leaders asked that question because they assumed that because they were the leaders any amount would be necessary and therefore would be allowed. The problem is under the Neoclassical order, this question had not been raised and the date was therefore unanswered. This is why the Great War is useful: it asked the unanswered question and provided a date because it ran out the time. The answer is in late 1917, even leaders came to understand that a new logic needed to be applied to this present war because the question was not “When will a short war be concluded?” but “When will a long war be concluded?”

From this interpretation, the fate of Neoclassicism was that there was a minefield in which submarines, tanks, trucks, and the Balkans all were deep pit stops any one of which could have made a Neoclassical leader vulnerable to overreach. That means that while Germany was uniquely positioned to be the country with overreach, because it was the country with the most to lose, England, France, Austria-Hungary, and Russia were also blundering about seeking to disrupt the delicate balance of the Congress of Europe. It only takes one misstep to send a Neoclassical piece toward Modern war because nationalism was key to maintaining the state’s readiness for war. This is because the amount of damage caused by

any particular mine could be enough to start a chain and for this purpose causality is not

required only a market.xiii

This does not look to blame leaders for engaging in a European war because the question had not been answered. The various major powers were pursuing their interest as they understood it. However, because of the tremendous increase in munitions and organization that they now employed, it was a different war than 1870-71. They thought in terms of a bygone age but in a specific way: they hailed the advancements in the industry without understanding that the disruption would go all the way to the top. Simply put, a monarch cannot be at the head of a Modern economy even if it was possible to be at the head of a Neoclassical economy. Instead of years to plan it took only months. Instead of years to put out howitzers, it took months. Instead of years to organize an army, it took months. The idea of a Regiment, which was all of the manpower in a specific area, needed to spread out the source because a Regiment could be destroyed meeting an area with no young men to replace a generation.

This means that we do not have to invoke the apparatus for causality in any specific sense because we are looking not for causality but only an indicator that a new form of logical system has reached the level of commerce and statecraft. Therefore, we do not need to phrase the question as “if X then Y” but only to look for a marker that a new system has replaced the old.xiv

This means that the Neoclassical was to be tossed out with the unit’s disdain for total war. However, the idea from the German and Great British governments was that economic control over the European continent did not need to have a basis in logic, because either the Army, in the German case, or the Navy, in the case of Great Britain, would allow control over the means of trade and manufacture. It is clear problem the archives from the First World War that Germany and Great Britain were the key players in that they had a system which they wanted to put in place that controlled not only the military situation but the economic, cultural, and scientific. This is why the two countries were antithetical to each other.

It did not work out that way because more than just industry was controlled by the logical basis: the sciences, the arts, the culture, the philosophy, and all that that entails need to be controlled on a basis that is of conscious and subconscious. This means that having an Army these that the conscious and subconscious control is based on discipline and order. But such a logical system does not allow for literature, science, and culture to exist except under a hierarchical state. In other words, every person who wrote a book must support the hierarchical monarch in almost every way.

This is not possible and is a logical contradiction. It also means that it is the systems that make it impossible war the Neoclassical to remain in gets present form even before World War I was declared. The pressure to alter the fabric of the social contract was in place at least as early as 1905. The Neoclassical came into power after the Revolutions of 1848-49 with revolutionaries claiming to revise the constitutional arrangements and specifically to bring suffrage to all men. The change of 1848-49 was not towards the liberal direction however, but to a new monarchy which gave only a few concessions when it had to but promised nationalism under a strong government with industry.

The Neoclassical left in disarray because its means were wholly inadequate to a total war state with the entire industrial power utilized to make weapons, concrete, barbed wire, and ships. There is a parallel: in the First World War, the aged leaders utilized young men and the civilian populace to pursue their goals using warfare. However, the young men who are conscripted, statistically speaking, are in favor of those rights which the older politicians must suppress. This means that the structure of a government is fundamentally in dialectic: the young people want greater freedom but the government conscripts them once to limit the same freedom. When the Neoclassical is in order, the wars are small and therefore there is a smaller number of casualties in small wars.

When the war expands, as it did in 1914 with the first Battle of the Marne and the secret plan for economic hegemony, it then spins out of control with each side responding to the other with a greater level of commitment until the governments start to snap: Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany all can mobilize more men than they can command. This means that there needs to be a new logical system that makes sense to both the leaders and to the civilians even if neither one knows what exactly this new system demands.

This is different from what historians now debate: the argument is how Europe engaged in the First World War when it should be “Why did all of the countries continue the war past its phase of a short war?” while it may be that some number of individuals can be held responsible for the First World War, though many historians doubt this, this book argues that the elites but that it would be a short war and if not then there was no limit to how much they could demand. Contrast this with the Franco-Prussian War, where the territories exchange were rather small, and the large change was to unite the German principalities into one German state. In World War I both the United Kingdom and Germany wanted to be able to control the trade of the continent of Europe which would in effect set them up for the next war with a huge advantage. Thus, the Franco-Prussian War was not going to change the structure of Europe, instead, it would continue on the Congress of Vienna model, whereas the First World War wanted to change the trade and economics and dismantle the Congress of Vienna. In other words, after the first battle of the Marne, all of the major participants wanted a change in how things were done. This means that everyone wanted a new world, but one in which their country had a better stake in running.

This is why the First World War was going to end up with a different world and why the older world which wanted to contain any such disruption had to fall. It further shows how the old order was not going to control the new order, because the old order wanted a new order controlled by the old means: monarchy, discipline, order, and restraint.

In 1914 Europe thought it was engaging in another Neoclassical war: a short sharp era of combat with a list of territorial demands and expansion of the winner’s role in postwar society. The Kaiser was interested in showing that Germany was now the most important state on the continent and the British were interested in preserving their strategic role in trade. This could be done so long as the military objectives were held in view. This was possible until the defeat by the Germans at the first battle of the Marne. The problem is that Germany had not lost this kind of war and did not understand that the change from a Neoclassical or to a total war was more than just setting new objectives which were all vastly larger scope and on the Entente side there was no vision of what they could demand from the Central Powers. As a result, each time one side wanted to negotiate a settlement the other side felt that there were still chances for a total victory.

In Philip Zelikow’s detailing of the lead people of America and Great Britain, people such as President Wilson and Prime Minister Asquith, one realizes that the actual decision-making power resides in a few hands at any given moment. Thus the logical system is in place because the people who are using language to communicate need to have a basis to explain their ideas and get some form of agreement for them to act together even if the action is unsuccessful.

And they are our different questions which are talked about in various different circles: while the people at the top spoke of “secret wish lists” this was far from the minds of the people generally the armies or dying in the trenches.xv This means that a logical system is necessary for the various parts of the organization to communicate, even if there is a layer of translation in the day-to-day operations of the overall structure. The fact that the upper levels required conscription is actually one of the subtle proofs that the top of the structure needs to have coercion in order to get young men to fight: the young men do not think it is logical that they should die for older men to win power. It also shows that differences can occur between members of a logical system, for example, in the UK the government was led by the Liberal Party, which was in theory willing to talk peace with the German Empire and the opposition was led by the Conservative Party, who took the harder line view that the UK should fight to the bitter end.xvi

The eyes and ears in this debate for the Americans were Edward M. House (1858-1938), a man very close to Wilson but who had very little ability other than the close personal discussion with other people that Wilson decidedly lacked. It is through his words that the president saw the tangle of relationships that Wilson wanted to cut through in order to get a chance for peace. Through the year of 1916, House tried to get the government interested in Wilson’s peace initiative and found a willing ally in Lloyd George. Lloyd George was interested in Wilson’s intervening to stop what he felt was an ongoing war which did nothing but in the spring of 1916, Lloyd George felt that the battles of the summer would have to be fought and in the fall negotiations could start.xvii The idea that the war had to continue to even put a stop to it shows that on the Entente side, the aims and methods of the war had changed from a short war to a long war because by 1916 the body count was known because of the bloody front of 1915. In other words, the war had been moved from a repeat of the Franco-Prussian War of 1871-72 to something completely different. And that again argues that the logical system which prevailed was different.

This meant that even when trying to stop the war, it had to be allowed to continue and chew up hundreds of thousands of men. This is antithetical to the idea of a short sharp war which is then concluded by peace negotiations where the victor gets the spoils. The people in charge of America and the United Kingdom could not see that not only was the war needed but the entire system which the war was an extension of had to close down because the Neoclassical order was predicated on keeping the jostling of states in bounds. But the order that came afterward did not reduce the casualties but increased the state’s tolerance of casualties, including civilian casualties which were intentionally afflicted.

i Howard, Michael. 1984. “The Causes Of Wars.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 8, no. 3: 90–103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41104274. Called “Howard”. 96.

-

i Stevenson, David. “Militarization and Diplomacy in Europe before 1914.” International Security 22, no. 1 (1997): 125–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539332 called Howard. ,159

ii Howard, 125.

iii MacMillian is one of those that hammers this most forceful voices. For Example, MacMillan, Margaret. 2015. Explaining the Outbreak of the First World War .

. But she also believes that the UK should not have been in “The Great War” which is against the British policy and all that that entails: allow no country to be the great state on the continent.

iv Lambert, Nicholas. 2015. The Short War Assumption. National WWI Museum and Memorial. London, UK.

. Called Lambert 2015. 2:30

v Lambert 2015. 6:30.

vi Lambert, Nicholas A. 2012. Planning Armageddon: British Economic Warfare and the First World War . Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt24hj4f. 185.

vii Boeckh, Katrin, and Sabine Rutar. “The Wars of Yesterday: The Balkan Wars and the Emergence of Modern Military Conflict, 1912/13. An Introduction.” In The Wars of Yesterday: The Balkan Wars and the Emergence of Modern Military Conflict, 1912-13, edited by Katrin Boeckh and Sabine Rutar, 1st ed., 3–18. Berghahn Books, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvw04j9c.5.3.

viii Pflanze, Otto. “Bismarck and German Nationalism.” The American Historical Review 60, no. 3 (1955): 548–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/1845577. 553.

ix William II, German Emperor. 1922. The Kaiser's Memoirs. Translated by Thomas Russel Ybarra. The Project Gutenberg eBook. Called Wilhelm. 223.

x Wilhelm, 225.

xi In German: Hollweg, Theobald von Bethmann. 1914. “Septemberprogramm” Reprinted: Wolfdieter Bihl, Deutsche Quellen zur Geschichte des Ersten Weltkrieges [German Sources on the History of the First World War ]. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1991, 61-62.

xii Mann, Heinrich. 1919. Der Untertan. Kurt Wolff Verlag, Leipzig-Wien. 1.

xiii This is because we’ve only a statement of fact to establish a marker. Quine, Willard Van Orman (1950). Methods of Logic. New York, NY, USA: Harvard University Press. Called Quine. 9.

“The peculiarity of statements which sets them apart from other legalistic forms is that they admit of two and falsity and may hence be significantly affirmed and denied.” Rather than a causative statement where the proof is not just to or falsity but the construction of “if X then Y.”

xiv And therefore, we do not need a causative if/then. See truth functions, Quine, 16.

xv Philip Zelikow. 2021. The Road Less Traveled: The Secret Battle to End the Great War, 1916-1917. New York: Public Affairs called Zelikow. 39.

xvi Zelikow, 40.

xvii Zelikow, 44.