Conclusion

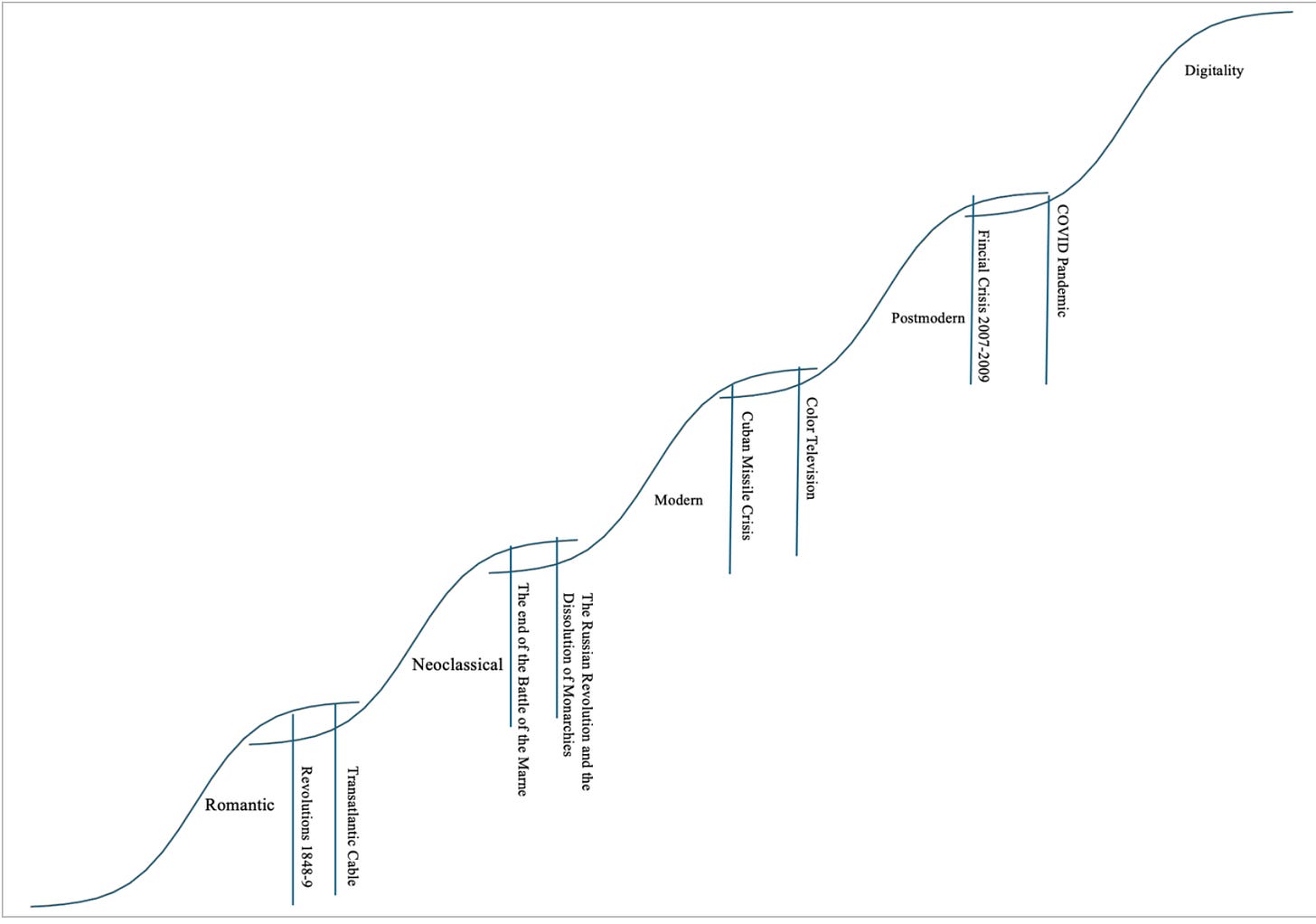

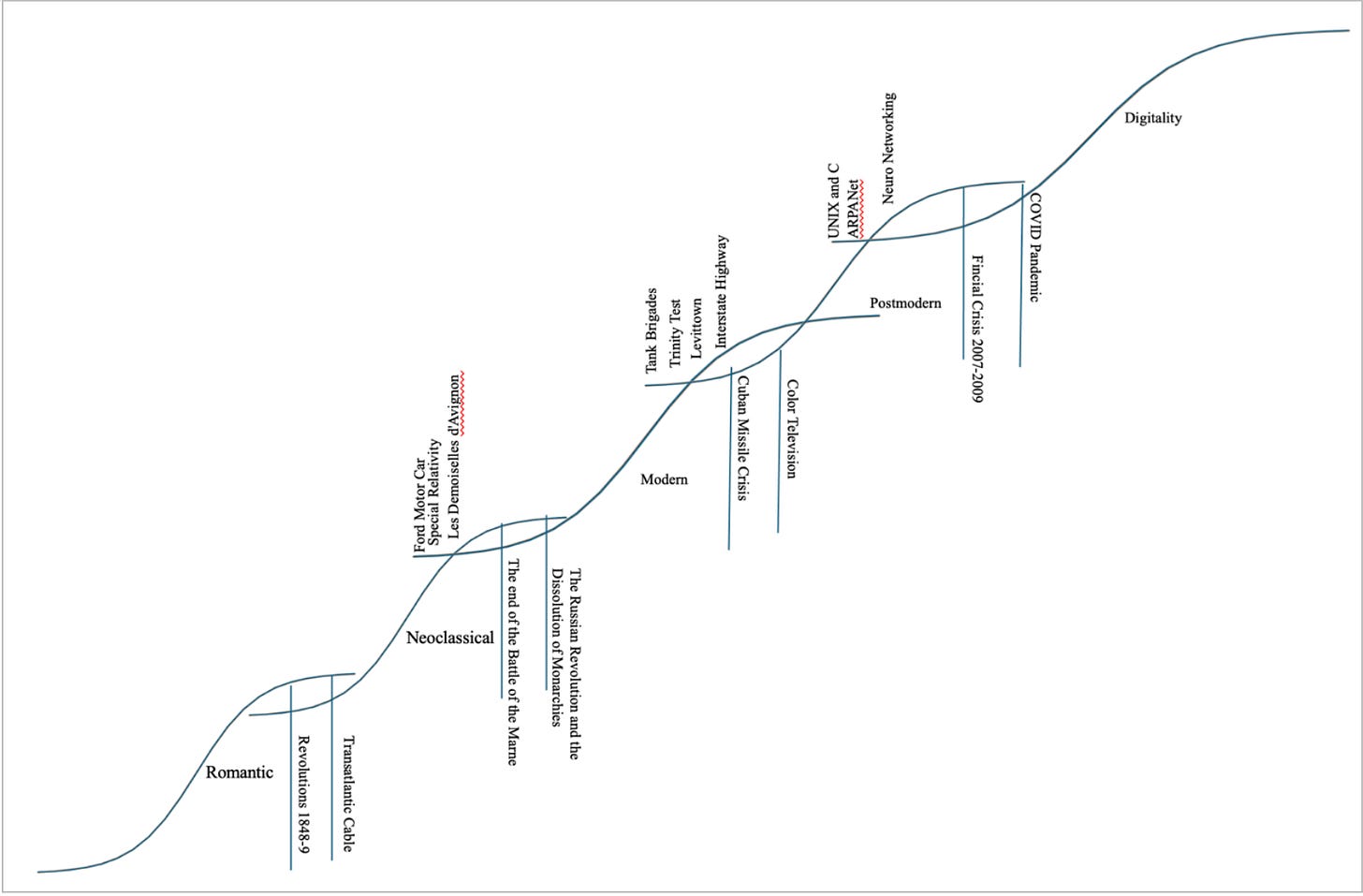

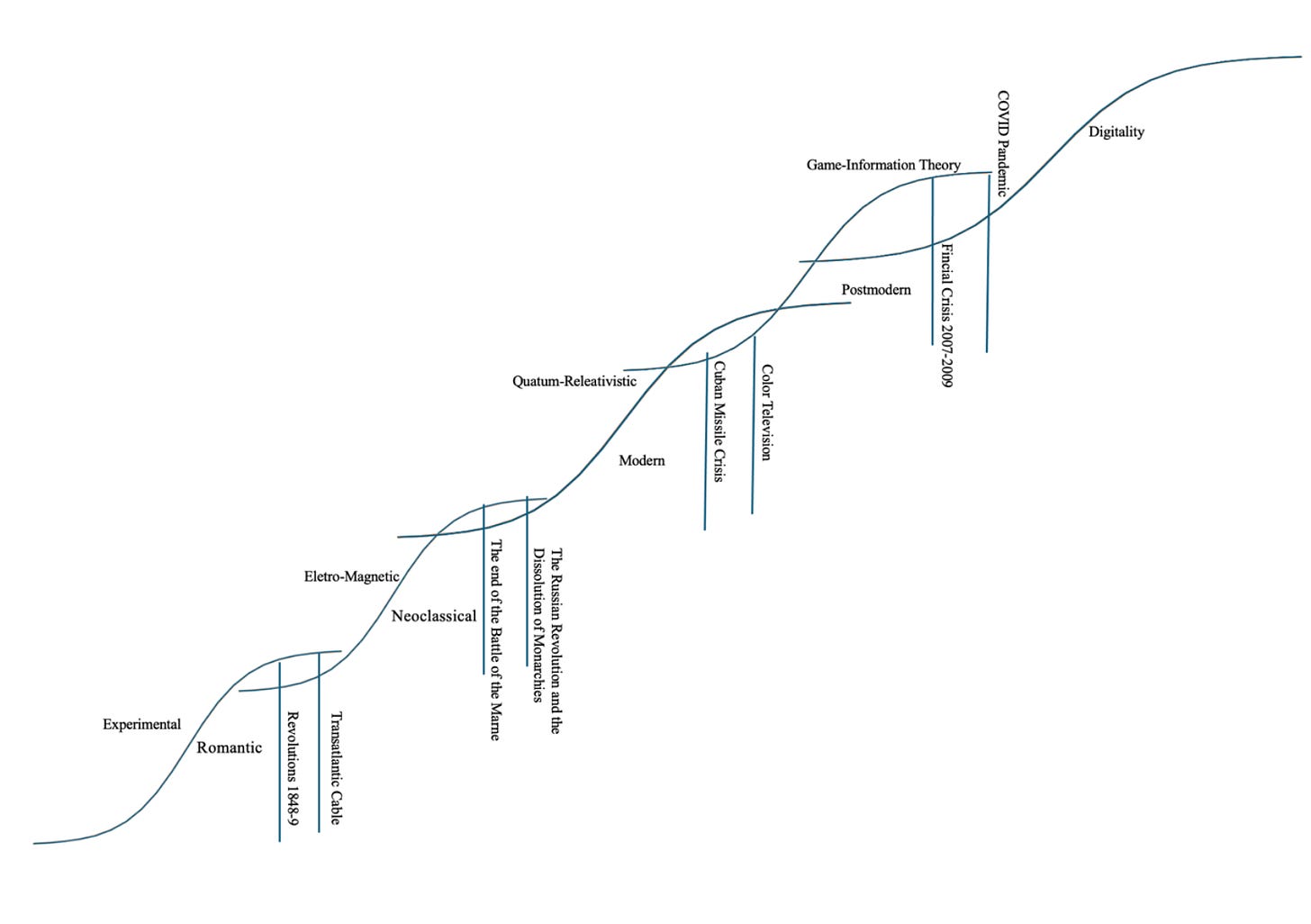

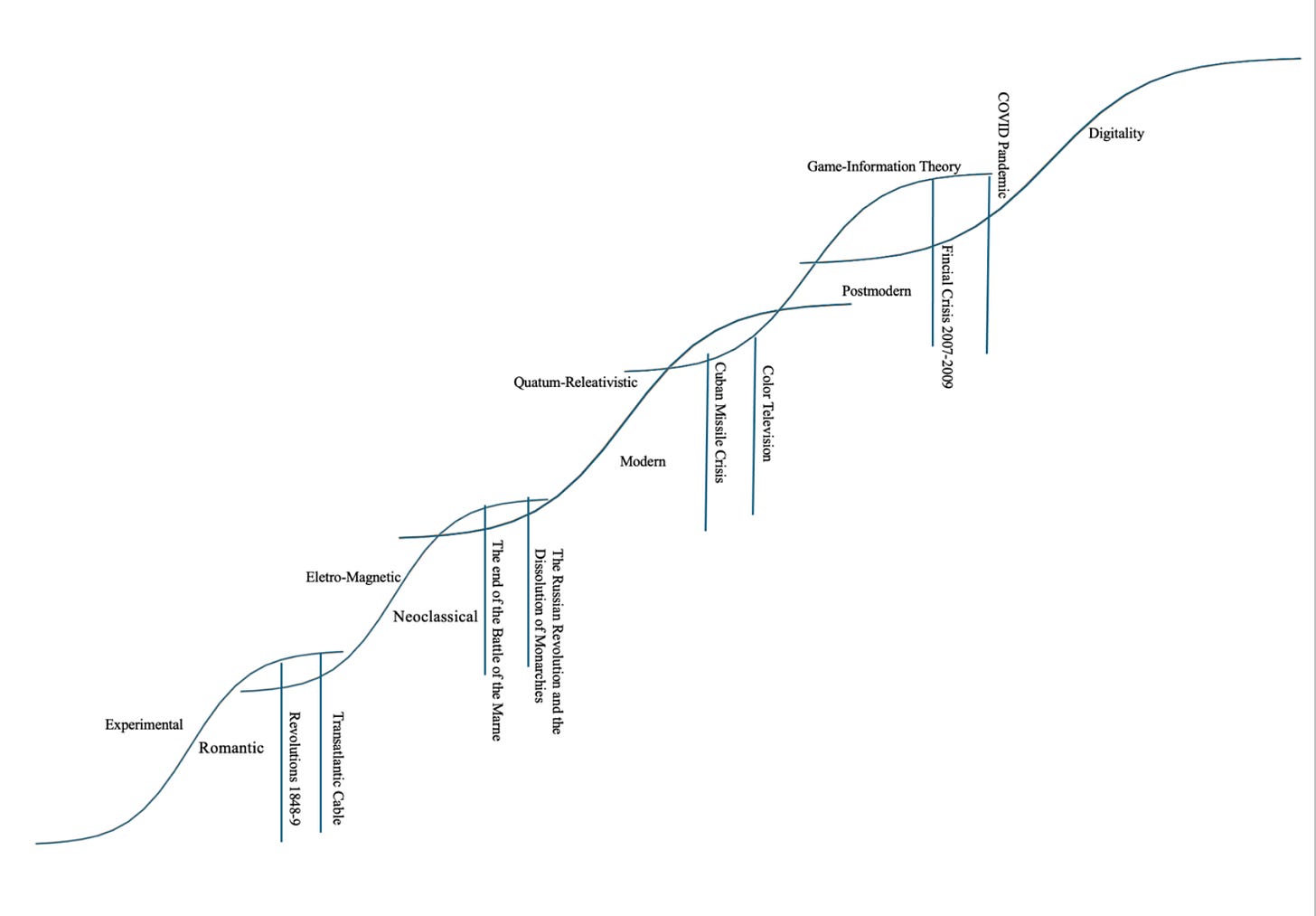

We now are capable of drawing out our sample Cultural System. First, we draw the beginning and endings:

We can then draw lines where the visionary moment occurs, with several events showing a pattern:

Though others will occur at the same time.

Note that each marker is defined by the convolution Of both the Population Pyramid and the probability distribution.

This then leads us to another observation: the people running a Cultural System at first are people who grew up under a different Cultural System. They may have been exposed to the underpinnings of the new system, but they are still members of the old system. At some point, the population pyramid shifts because as people get older, they produce fewer children. This means that over time the population that is coming of age does not see the benefits to the older system as much as the older people. In a sense, the younger generation knows only what they have been exposed to whatever that might be. That means in the middle of a particular Cultural System there is a change from the old system to the new system.

That means that in the middle of a Cultural System, there is a change where the younger population sees things in a different light. That means that we should look at the middle part of a Cultural System, and see the inventions, creations, and political systems which were not possible under the old Cultural System but are entirely possible under the new system.

An example of this is found in the Neoclassical era: near the beginning of the Neoclassical era there was a discovery by the eventual Lord Kelvin which made possible the running of transatlantic telegraph cable. Specifically, it was a theory about electricity. In the middle part of the Neoclassical, a more general theory was put forward by James Maxwell (1831-1879), first in an abbreviated form in 1865 and giving all of the work that was done in 1873. Later Oliver Heaviside used more sophisticated means to reduce Maxwell’s 20 equations to only 4 starting in 1884 and then published in The Electrician starting in 1893.i He used vector calculus rather than previous attempts including quaternions The reason this is a central discovery of the Neoclassical era is that it takes the mathematics including concepts like curl.

But how does one pick middle-period advancements from a those that merely happen between the beginning and end? The procedure is to first examine mathematical concepts discovered at the beginning which are important to the Cultural System which takes place. For example, Game Theory was important for the cracking of the enigma code and similar codes based on the same idea, so can be formed as one of the seminal Postmodern/late Modern discoveries, then when it was applied to nuclear war, it suddenly became a key Postmodern way to deal with the statistical and mathematical problems. Hence the key idea is that an early mathematical problem becomes the centerpiece of an explosion of ideas. The same can be said for the electro-magnetic discovery of Maxwell because in this Cultural System, one of the key discoveries that made the Neoclassical important was the discovery of an electrical system which then created Maxwell’s discovery that magnetism was in fact part of the same phenomenon that electrical was. When looking at the central discovery one forms a three-part discovery: in the early phase, a mathematical means is found, in the middle section, a more general mathematical sense is discovered and new inventions, out of this more general sense, and then at the end of the period there is the codification and simplification of the fundamental idea. For example, the original form of Maxwell’s formula was complex but then Heaviside simplified it with vector calculus which formed the “classical” way of thinking about physics.

This means that we can introduce a new sigmoidal curve that pinpoints an exact moment when the moment where the revolutionary mode becomes the evolutionary mode in markers. This then creates a larger picture of what a dominant cultural theory works from: many of the core discoveries whether artistic, industrial, scientific, or mathematical will relate to the underlying theme that is present in the central idea. This means that in this Cultural System, the idea is the transmission of information by means of a new concept which elaborates in different ways.

This means that Digitality does not have a central theme yet because it is still finding its way as a Cultural System evolves. Quite simply be generation that is born in the Digitality is still observing and will make discoveries as time goes on. we can say that the Neoclassical was the hero of vector calculus and the x2/ duopoly of physical constants.

Whereas the Modern period was about that there was the smallest unit to space and time and the discovery that the Strong Force was not an x2/ force but actually grows stronger until it breaks apart. That is, it was not in line with the other forces that had been discovered. At the same time, the Postmodern was interested in social dynamics which formed x rather than x2 leading to a game theory formulation where there are two linear forces that are opposed to each other which leads to the Nash equilibrium which is the central idea in economics and other fields.

The Romantic period in this Cultural System is the 0th Cultural System and therefore has the distinction of being the progenitor of the means by pitch the Cultural Systems will progress over time. In the previous era, which I will call the Enlightenment, one of the key points was to conceive in the mind a pure set of values. For example, circles were perceived as purer than another eclipse, and therefore the stars and the planets should move in circular fashion as they progressed. This inductive from the mind was central to almost all “scientific” discoveries going back at least as far as the ancient Greeks. However, there was an alternative view that was deductive reasoning: looking at the world and seeing how the world functioned. This became a point of conflict when Newton and Leibniz both discovered the calculus, and in particular day found that integral calculus was the opposite of differential calculus. Differential calculus had been known about since Archimedes but no one had realized that if one could differentiate the function then one could integrate the same function.

This led to the discovery of astronomy, and new forms of geometry, and … then it waited. It was weighted because several key concepts were opposed to the idea that one should look at nature for the basic principles. This included European religion, which proposed a “God” and European political systems which proposed that a single person should be the ruler of a nation. However, by the late 1700s, an explosion occurred resting on the idea that emotions should be as equal as logic, and that logic should be both inductive and deductive in pursuit of the truth, wherever it would be found.

The idea had been building for many hundreds of years, the Babylonian and ancient Greek writers would occasionally use it, but a good case can be made for Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (c. 965 – c. 1040) being one of the first who used what would later be called the scientific method in his كتاب المناظر (Kitāb al-Manāẓir) which is translated to English as “Book of Optics.” This means that the scientific method has been used even recently but it was not the starting point for the scientific nation as we understand it today.

What changed the nature of the debate was the emergence of writers who were both scientific and philosophical. Indeed, at the time the word philosophical comprised the rigorous logic of philosophy with the exploration of properties found in nature. At the time there was no new science per se. But then came Immanuel Kant who argued for a philosophical distinction between “notions” that had certain properties which he labeled Transcendental idealism. In his Kritik Der Reinen Vernunft (Critique of Pure Reason) he made a distinction between sensory experience and the logic of the true form of the object which is only accessible by logic and reason. In other words, merely experiencing an object without reasoning is insufficient. And this he joined empiricist philosophers such as John Locke and David Hume with rationalist philosophers such as Christian Wolff to reduce a synthesis.

This synthesis would eventually become known as the scientific method in the 1930s. but in the context of the Romantic period, Kant inspired scientists and writers to examine the sense in the light of reason and that started deductive reasoning. Also emotions represented a different form of reasoning than the mind. This idea then is how experimental philosophy became the default in the Romantics’ worldview and the discoveries of geology came from the idea that deducing from nature is better than abstracting from the mind. In addition, Kant proposed a model for the origin of the solar system which is still recognized as influential in cosmological circles. This meant that he was not only a philosopher but also a scientist.

It seems that in this Cultural System, several thinkers who were previously aligned with the Enlightenment, have both an Enlightenment era logic with Romantic era deductive reasoning. In other words, figures like Kant and Rousseau are not either/or but both/and.

In the wake of Kant and Rousseau, a new series of philosophers rose up to try to join inductive and deductive reasoning such as Hans Christian Ørsted (1777-1851) who believed that the electrical force was the same as the magnetic force, and made progress towards the unification of the two but did not solve the problem.

This belief in the unity of the powers of nature was characteristic of the German Romantic school of Naturphilosophie. Both Oersted's metaphysical speculations with their echoes of Naturphilosophie and his extensive laboratory experience deserve more general recognition; for, contrary to the interpretation of many writers who have touched on Oersted and electromagnetism, his discovery was no mere accident.ii

The problem was that Ørsted did not have mathematical tools to effect the proper synthesis since the magnetic is 90° of from the electrical. But the nature of Naturphilosophie was embedded in the science, placing a new emphasis on experimental science in addition to the inductive science. It was the combination of the two that created a new version of scientific reasoning.

This is why I say that the Romantic period does not have the full measure of the Cultural System because it does not transmit information to everywhere in its domain. Thus the telegraph was vital at the end to its transmission but it lacked the electrical theory and engineering subtleties to lay down a transatlantic cable.

This gives us a sounder theory as to what breaks apart an old theory and forms a new theory: the old theory cannot describe, or at least not easily, something that the new theory can more easily describe. This means that the Postmodern Cultural System relies on game theory, information theory, and statistics, and uses those ideas in almost unlimited forms to explain the world. However, climate change does not easily work out in this form but instead uses stochastic analysis to relatively easily predict what the probable temperature will be in 70 years’ time. In other words, there is a new system, that system easily solves problems that are hidden from the old system, and if the model presented in this book is correct, there will be other discoveries made with this concept that are as yet obscure, obtuse, and problematic.

Summation

In the first part of this book, a series of steps were outlined to give a mathematical means of describing Cultural Systems. This was because unlike a vast majority of animals, humans rely on culture rather than genetic psychology. With most animals, but not all, the genetics are built in that create a psychology for the animal. This is not to say that they are merely automata but that the lessons are programmed in and the ability to decide is sharply restricted. With Homo sapiens, a greater degree of freedom is allowed, and several adaptations create a culture which is then used by genetics to adapt to the local environment. This means that Homo sapiens are one of the few creatures that can adapt to a large fraction of the environments.

Taking this vector algebra approach, we then explore how the population pyramid arises from the vector algebra and creates a condition whereby the young spend a great deal of time learning from their parents and others how to behave. This is an adaption where the genetic markers allow the young to learn rather than be programmed. It also means that there are at least two approaches to learning: a bottom-up version where the young learn from their elders, and a top-down where the members of the society who have a greater degree of freedom impose restrictions. However, the xaotic nature of the Lorenz process means that a wide variation will be produced. This means that the results of either the bottom-up or top-down approach will have unexpected consequences in the actions that are taken.

The other problem seen by mathematics is that the structure of society, which remember is necessary because of the genetic outcomes, will change because Homo sapiens are able to make objects which create a discontinuity. In other words, we make stuff that has a larger outcome than would be expected from the tools needed. A simple example is recording: a single event can be distributed over a larger number of people than would be possible by oral transmission. Architecture, writing, artwork, printing, recording, and transmission of speech are all other examples and more will be produced over time.

This creates an S-curve, called a sigmoidal curve, whereby innovations that are similar to other innovations can be reached far more quickly. But it is an S-curve because the innovations produced run out, and a new approach is evolutionarily selected to move forward. This means that a series of S curves are produced where one S-curve is dominant until it makes to many mistakes, and then another S-curve will take over to run its course.

This means that an S-curve can be divided into visionary, revolutionary, evolutionary, late phase, and nostalgia components that trace out the S-curve as it traces out. The markers for the S curve can be distinguished by their conditions of discovery. This means that an S-curve has a predominant symbolization. This symbolization can be described by first pointing out the beginnings and endings of the S-curve, and then locating when the Revolutionary to Evolutionary change takes place. This marker is one of the changes that the S-curve makes. For example, in the Neoclassical the problem of unifying electrical and magnetic forces were when solved by James Maxwell and reduced down by Oliver Heaviside two a short description of the force of electromagnetism. But at the point at which it had gained its highest perfection, there were problems that made it unworkable. Thus, a new Cultural System replaced it.

Because the mechanisms through which activities of Homo sapiens are interlinked it is not just scientific knowledge but knowledge in general: that is painting, cinema, music, novels, and other features of the Cultural System move in sync with the scientific and the net approach is that one activity influences the others. This means that there is a gestalt movement that runs through the entire society that is under the influence of a Cultural System.

This means that a Cultural System can be described as a series of S curves going from visionary to nostalgia. It also means that many Cultural Systems can be described each one focusing on individual problems that the historians and others are focusing on. Remember, that a Cultural System is Xaotic which means that the outcome is unknown. This is a benefit not a bug in the Cultural Systems theory.

What this means is that a definitive event cannot capture all of the nuances in a Cultural System, but a marker can be seen from its effects. For example, the end of the first battle of the Marne in the German high command is such a marker: it shows that the direction of the war had been turned from a short war to a long one, and from a short list of objectives to a much lengthier one. There were obviously other events at the same time which made the same move. Thus, we have a marker, not an event that changes everything. That means that other markers may be used but these are the most compelling.

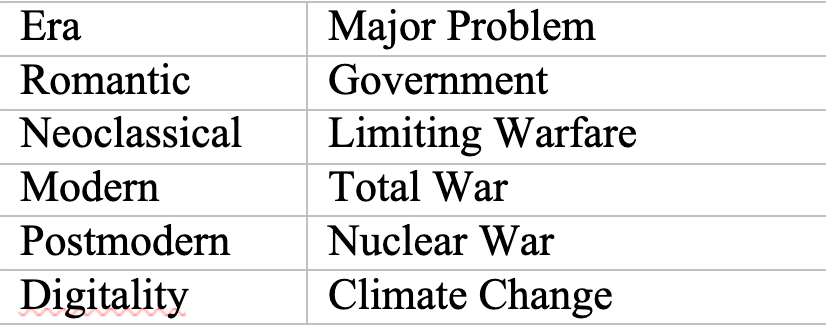

In every era, there is a problem that dominates all of the others. Currently, in the world of Digitality, that is Climate Change, and in the Postmodern that is nuclear war, the Modern is obsessed with total war, while the Neoclassical sought to limit warfare to a negotiated settlement, and of course the Romantic was about whether government should be by the few or the many.

The example theory in this book is devoted to the events of 2024. Naturally, these events will be acted out and another theory will be necessary for another time. But, since the mathematical formulas are based on mathematical structures rather than argument, that theory can the constructed in the same way that the example theory was in this book. It also will be useful to see what effects were dominating the conversation in this era as a guide. The general patterns of this example theory may not be the same ones as others

With this history becomes more scientific and perhaps will be a science, but that is a problem for another book.

The original idea was that genetic systems did not act on human beings the way they did on most other creatures. We noted that there were other creatures that acted in a similar way in that they did not use genetics exclusively but allowed the offspring to learn from Cultural Systems as well. This meant that we needed to use a mathematically oriented algebra to gain insight, noting that history is at least to some degree a version of biology. This led us to linear algebra as the most promising way to mathematically analyze history.

We began by using linear algebra to model vectors which showed individuals in some direction. We also noted that the Dirac delta function could be modeled as a conception function and that the majority of births to women are between certain ages. This led us to conceive of the conception function as being a population pyramid with babies coming from women of a certain age. This led us to conceive as a Fourier function a bottom-up culmination of events. But then we looked at the Laplace function and saw that while there was indeed a bottom-up function there was also a top-down function that pushed the population in a different direction. We found out that markers would be better than other forms of trading ideas. Thus, the markers were a substitute for how to divide history. This makes sense because history is far more complex and has far more variability than can be constructed by other means.

From there we explored PSA and Xaos theory showed how this action is Xaotic and how this Xaos could be modeled in the same way that was used for basic linear functions. It was at this point that we described a sigmoidal curve as the Cultural System and that at the beginning of a Cultural System, there is a predominant curve ahead of a Cultural System and then when the Cultural System nears its end there is a new Cultural System that solves certain problems while it creates others.

This then led us to an example Cultural System which was based on the idea that a Cultural System at any given time would be expiring, and that a new Cultural System would be born. But if a Cultural System dies it must have had a beginning with systematic ideas both intellectual, industrial, cultural, and political that fit together in some pattern. We then also discovered in our sample Cultural System that there is an endpoint based on the reality that the Cultural System is based on certain ideas that run out over time.

We have not examined in this book the flock mechanism but clear this needs more attention: the flock will be generated out of simple linear algebra forms. This will be useful for epidemics, warfare, and famines which occur at regular intervals and thus make a top-down indentation and therefore will show up in Population Pyramids. This feature appeared in the Neoclassical period and changed over to both the Modern and Digitality eras.

This then is a summary of how a conceptual system forms a holistic view of Cultural Systems in history. It is meant to not replace history but to add mathematical precision to the arsenal of ideas that history uses to explore how historical events occur. This is far from a complete theory which is why at least two other Cultural Systems will be explored in the coming books. But the objective is to do the same thing: find a pattern that has a beginning and an end, shape the pattern by top-down and bottom-up parameters, find markers that explain why a particular era is important for the Cultural System, and then look at the Cultural System and see if there is missing gaps and explore if those missing gaps need attention or, in the worst case scenario, break the conception altogether.

This of course means that history has become a more mathematically defined science than was true before. It means that some historians will need to take linear algebra and complex dynamics to understand how a system gets created and explored. This might be to many a double-edged sword in that mathematics may confuse subjects as well as explain matters more clearly. But the step-by-step explanation of why mathematics can be a tool for the historian argues that at least in some cases, the effort is worth the symbology.

Acknowledgments

Of course, many people have helped with creating this work in its current form but I would also like to thank:

Gilbert Strang, recently retired from MIT.

Steve Strogatz, Cornell, and the author of his excellent book on Xaos theory.

Steve Burton, who teaches at my grandfather’s alumnus.

Of course, all errors are my own And I cannot clean to know what these individuals think of this work, perhaps they feel it is crazy and absurd.

i A clean version is presented in Hampshire, Damian P. 2018. “A Derivation of Maxwell’s Equations Using the Heaviside Notation.” Philosophical Transactions: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 376, no. 2134: 1–13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26601861

ii Stauffer, Robert C. 1957. “Speculation and Experiment in the Background of Oersted’s Discovery of Electromagnetism.” Isis 48, no. 1: 33–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/226900. 33.