Organization of a Discipline

One of the key concepts that the Romantic grappled with was the Organization of an entire discipline. A good example is found in Linnaeus and is organization of species. Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778) published Systema Naturae starting in 1735 and Species Plantarum in May 1753. But it was in the 10th edition that he sat down the system for naming plants and animals.i His bent was practical rather than theoretical in his attempts to structure taxonomical relationships in a logical way.ii By 1778 the “fundamentals of the limiting system of binomial nomenclature” was established.iii Indeed the name binomial nomenclature means that an animal or plant is named by a generis and species that spreads over geography and time as well.iv

Within decades the establishment of taxonomic ordering of species was well established, with a rearguard fought by figures such as Buffon, who had taken over those studying biological sciences.v But what is missing is a top these of theory That links all of the sciences together and within each one links each sub-discipline to its place in the larger world. This was because in the 1700s there were pieces missing and there was a belief that God supplied the missing apparatus. This is very different from today when people refuse to believe and must believe the place of the theories of science, they believe that God still supplies the missing pieces and that in scientific belief is equal but wrong.

But in the 1700s, there were still missing pieces to the scientific side of the puzzle and therefore God could supply those missing pieces. It was still possible to believe that there was a metaphysical force that bound together all of the physical forces that were described. In the 1700s things such as electromagnetism, meteorology, plate tectonics, be ordering of elements in the ordered way, and particle physics, were all yet to be discovered, and therefore scientists could still believe that there was a metaphysical force that explained all of the details which were still yet to be discovered. But there was also the mathematics which was still not well understood, even the calculus was known to be unstable in the mathematics of the time. Things like quaternions, topology, a new understanding of algebra based on rings, and several other topics were still yet to be discovered and this meant that even the calculus, Europe’s major invention in the mathematics, was still known to be loosely bound. What this means is that in the 1700s there were, as Feynman would say of statistical mechanics:

This Fundamental law is the summit of statistical mechanics, and the entire subject is either slides down from this summit, as the principal is applied to various cases, or climb up to where be fundamental law is derived and the concepts of the equilibrium temperature T clarified. We will begin by embarking on the climb.vi

What this means is that in contemporary times a few key insights form the basis of the theory, and we can look at specific cases and see how the theory is used, and at the same time, explain how that theory is derived by similar means to underlining theory which governs it. Neither of these two directions was immediately apparent except for physics, which was based on Newton’s kinematics and theory of gravity and the astrophysics that derives from this.

This means that Linnaeus would be diminished in both taxonomic intricacies and with a theological discussion of God.vii Indeed Linnaeus was referencing God in his works.viii This is different from contemporary science in that instead of a physical reason for each thing’s existence there is a metaphysical reason, instead of an overarching theory that needs to be filled out and expanded with other physical theories the ultimate reason for the object existence is a metaphysical theory which was “God,” however God is understood. This was a difference between the Enlightenment and the Romantic: God was present, even if only for others, during the Enlightenment but nature replaced God in the course of the Romantic movement.

Because the Romantics were struggling with exactly the role of science even the basics of science were not understood. This is where Kant (1724-1804) comes in, in that he proposes “universal imperatives,” not just to science, but to all of human endeavor:

If it becomes desirable to formulate any cognition as science, it will be necessary first to determine accurately those peculiar features which no other science has in common with it, constituting its characteristics; otherwise, the boundaries of all sciences become confused, and none of them can be treated thoroughly according to its nature.

The characteristics of a science may consist of a simple difference of object, or of the sources of cognition, or of the kind of cognition, or perhaps of all three conjointly. This, therefore, depends on the idea of a possible science and its territory.

First, as concerns the sources of metaphysical cognition, its very concept implies that they cannot be empirical. Its principles (including not only its maxims but also its basic notions) must never be derived from experience. It must not be physical but metaphysical knowledge, viz., knowledge lying beyond experience. It can therefore have for its basis neither external experience, which is the source of physics proper, nor internal, which is the basis of empirical psychology. It is therefore a priori knowledge, coming from pure Understanding and pure Reason.

But so far Metaphysics would not be distinguishable from pure Mathematics; it must therefore be called pure philosophical cognition; and for the meaning of this term, I refer to the Critique of the Pure Reason (II. "Method of Transcendentalism," Chap. I., Sec. i), where the distinction between these two employments of the reason is sufficiently explained. So far concerning the sources of metaphysical cognition.ix

Unto this point, we have been using the metaphysical from our standpoint to distinguish between a physical explanation and an explanation that involves God. However, Kant is using the metaphysical from his perspective as a blueprint for what kinds of physical manifestations can exist to structure the real world. While clearly a member of the Enlightenment, his ideas caught on with the Romantic and therefore he was an influencer of, but not a member of, the Romantic movement.

This shift was felt both in the short term and farther afield. The idea that God was the meta-force that explained the inner workings of the universe was part of the Enlightenment’s core being. When Kant disrupted this which then opened the way for a new basis for the physical sciences. This does not mean atheism, but the understanding that the physical world needs very little movement from a God figure. What this means, paradoxically, is that there are movements to place God at the center of the universe as time goes on. But again, this is much more in the Neoclassical movement when the threat to God’s existence was felt to be a threat. But this again leads back to Fichte, who was a devotee of Kant, even to the point of some of his critics saying he was equally verbose and unreadable.

One of the most important figures in this process was a mathematician called Augustin-Louis Cauchy born in France but with a delicate situation with those who controlled. One of the problems of the Romantic is that it had long since reached the limit of Newton and other figures of the 1600s and 1700s. and it had two figures who were determined to bring about a new basis: one of course was Gauss - with his manyfold contributions and the second one was Cauchy. Where do they fit in a period scheme of ideas and action? In Caucy's case, the combination of bringing an idea to the self in mathematics is very much like Goethe’s own self as the manager of all things. And one must remember that Cauchy the accused to take an oath of allegiance, because he regarded the liberals after the Revolution of 1830 as anathema. It should be remembered that radicals and reactionaries are swept up in the questions of the time in politics. He went into exile rather than face the consequences of opposing the new government and only returned eight years later, he joined his family in 1834 in Prague.

His life in mathematics was broad and deep - but perhaps his most work is on “infinitesimals” and setting calculus on. New footing is based on the idea of a limit as the fundamental idea. When students are now taught calculus, they are drawn into an excursion about δ/ε which seems as if it has no bearing on taking derivatives or integrals. But this is not the case, because in order to be able to actually prove the fundamental theory of calculus, the proofs need δ/ε for their basis. Epsilon is essential for proving the rigorous version that made it possible for calculus to send from algebra. And as Grabiner explains, the fundamental idea is that the derivative is the inverse of the integral.x The problem of algebraic inequalities word and a direct way to the fundamental error of calculus, because it showed that the integral was the inverse of the derivative. With this as a basis, one can rebuild calculus on a rigorous basis as being the next step in algebra. The problem was that be proof of this fundamental theorem of calculus a great genius to see that needed several ideas to solve: for example, the mean theory of integrals of Lagrange. This is why actually proving the fundamental theorem of calculus requires basically a semester of work: even explaining the proof requires a chunk of time which is beyond the first-year calculus student. And Cauchy was the genius who proved it.xi Until this point in 1823, calculus was not grounded but had to be assumed. Newton and Leibniz both realized that what was to become calculus was so important that even if it had to be assumed, which was contrary to the Greek idea that mathematics should be unified, it was worth the price for the calculations that flowed from it. The Romantic then serves as the root for things such as mathematics and geology to be rigorously shown as part of the vast tree of knowledge coming from underlying principles. This was a new project that found sustenance from the greats of mathematics but flowed through every aspect of human endeavor. Thompson’s formulation is flowering from the stem of Cauchy roots and the 1812 Analytics Society stem.xii

Back to the Beginning

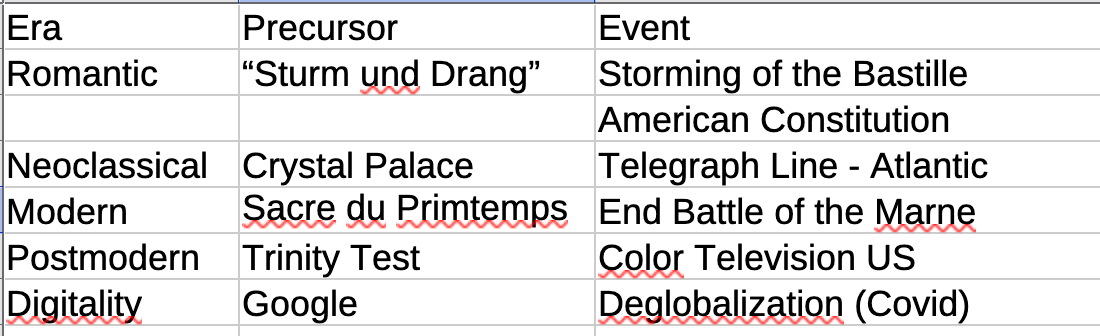

This brings us back to be beginning: is there a specific moment when the elites found that a new system had occurred? The two revolutions that began the period clearly call out. While the American Revolution was indeed a signature moment, it was only with the French Revolution that the elites realized that even a long-established monarchy could be overthrown. In that sense, the American Declaration of Independence was the warning shot, but the storming of the Bastille and the American Constitution were the signals that the world had indeed changed. This makes it clear that the movement starts but it is not coherent enough until the large mass of people can understand its principals in a manifest way. Again we see that the production of art and sciences, which are the domain of a single individual or a small group of individuals, comes before the realization by the elites of a new system.

This means that we can add another line to the list:

And we can assert that while the development of a movement comes as events demand a different way of thinking, both the development and the event happened relatively quickly.

This means that within these metrics ideas percolate constantly but some breakthroughs change the way that people who live under them think about the world as a whole. This is not that this is the only way to divide history, but it is a way to demarcate deeper trends and when exactly the new way of thinking becomes predominant.

This also applies to industry. Alignment is the idea of attaching objects to square us and then by manipulating those squares one could manufacture objects, for example, textiles. In theantic, the idea of having reusable parts so that when one part does not work you only have to place the part and not the entire product. This is important of course to military hardware such as rifles. And other important point is that coal became a fuel for manufacturing. William Blake writes this in his unfinished The Four Zoas:

The time of Prophecy is now revolvd & all

This Universal Ornament is mine & in my hands

The ends of heaven like a Garment will I fold them round me

Consuming what must be consumd then in power & majesty

I will walk forth thro those wide fields of endless Eternity

A God & not a Man a Conqueror in triumphant glory

And all the Sons of Everlasting shall bow down at my feet

First Trades & Commerce ships & armed vessels he build with laborious

To swim the deep & on the Land children are sold to tradesxiii

Here Blake charges the universal empire is born with fuel and blood whose children are traded. One can find many examples in many other poets reflecting that agrarian life has been disrupted and that refugees are sent to towns and cities to work in the new factories. The crush of industrialization in the Romantic time period is an acceleration from the middle 1600s, when coal was used as a source of heat but in the late 18th century and early 19th century, it became a source of fuel to make weapons and cotton cloth. And the agony of the workers was accelerated because of the new source of energy. This too is part of the Romantic movement and often it was despised by the poets and novelists. It is in this moment, for example, that Frankenstein fuels in South as a God when he creates a creature. Thus you can understand why in some sectors of society God is not a benevolent figure if his product is to die as a child in a factory.

In the Romantic epoch, there are many ways of thinking about things but they are bent towards what may be called the zeitgeist of the time. This zeitgeist is often influenced by certain ideas that come into fashion. These ideas fight with the older ideas and, as Dirac said, they progress to the future “one funeral at a time” - gradually the people who hold the older ideas die off and our replaced by newer ideas. These people tend to generate new ideas which are in line with the new zeitgeist. There is a point where a new discovery or event happens that does not accord with the predominant zeitgeist and forces a new aesthetic to come into play. What the event signifies is that a large percentage of the people acting find there is a difference between what they want and what is expected. In this moment the storming of the Bastille and the American Constitution our such moments. The American Constitution is particularly so because the representatives of the states were only made to make changes to the existing structure, but it became clear once they had that only an entirely new Constitution would be adequate for their ends. Then what was written had to the gratified state by state, bus ensuring that there was a well among the electorate, which was not the same as all of the people at that point, for such a change.

What can we say were the primary ideas of the Romantics? The first idea from Rousseau, in his old guys of a philosopher rather them the composer, is that external observation was fundamental to understanding the processes of the world. Before then a supposition was set up as the default and deductive reasoning was used to find out the state of the world. So, planets were described in perfectly circular orbits because a circle was the interest of forms. But then Keppler showed that the orbits of planets, comets, and moons orbited in elliptical orbits. But this was still the exception. But by the Romantic, it was the starting point for a variety of disciplines.

Two of the primary centers were that God created the universe, and if he did then it was almost inevitable that catastrophism was the way that things could happen so suddenly, the other one was reason could the used to divine all that was leading to a mechanistically driven world. But with the idea that nature was supreme and observation could deduce the organization of nature, it was observed that most changes occurred by gradual movement of the same kinds as one saw today. This meant that nature replaced God, and integration and feeling needed to be placed with reason.

This does not mean that people stopped believing in God, though some did so, but it did mean that there was an increasing separation between the God of the pulpits and the nature of the fields. With these cardinal points: nature, passions as well as reason, the multitude of peoples rather than a divine monarch, and a disdain for ordained knowledge that did not have the backing of an inner nature, the Romantic set a new course: there were revolutions in America, France, and Latin America, a larger electorate even when there was no revolution, uniformitarianism in geology and ultimately in biology, Infinitesimal and continuity in mathematics and an expanded range of notions with regard to what is mathematical nature such as Quaternions, Hamilton Mechanics, and a wider sense of what calculus could do in engineering and physics. When backed up with the novel, which came to be the dominant form of written fiction, and with had the subdominant as opposed to the dominant in music the Romantic swept the field until the failed revolutions of 1848.

Just as a logical system comes to fruition with an event that shows that the old system has been worn out, the end of a revolution is with the same force. It is not always the same moment as the beginning. The revolutions of 1848 were clearly meant to show that a liberal revolution would not work at the time. In another book, I shall show that a conservative liberal revolution, which I call the Orange Revolutions, would take its place, but that is for another moment. The revolutions of 1848 were Democratic and liberal in nature but even when the revolution succeeded and was usually overwhelmed by an Imperial regime. In the end, the revolutions of 1840 were a bookmark to the revolutions of America and France at the end of the 18th century. Part of the problem was that passions and feelings could not work as a governing principle thus when the revolutions of 1848 took power. The ideas of democracy, that is elevating the whole of the male half of the population, and liberalism, which meant at very least the consent of the governed, were permanent in France, the majority of the states which would later comprise Germany and the city-states of Italy. But the willingness to revolt is not the same thing as effecting a revolution. However, the old “Ancien Regime” needed help from the class which had grown wealthy by manufacturing to defeat the revolutionary forces in all but a new place such as Sicily. Thus, it was not a Bourbon monarchy that took the throne in France, it was not the plethora of states in Germany or Italy, but a new monarchy that needed more power to control the masses underneath them.

The Romantic was over, but a new consensus came to be, this consensus I will call the Neoclassical because it was not a return to the old regimes bought a new system based on property and commerce.

Romantic Markers

The Romantic age is a precursor, never having reached a point where communication became relatively instant between individuals. That means that it is in a sense a failed movement, that crinkles on thin air because there were attempts to achieve instantaneous communication.

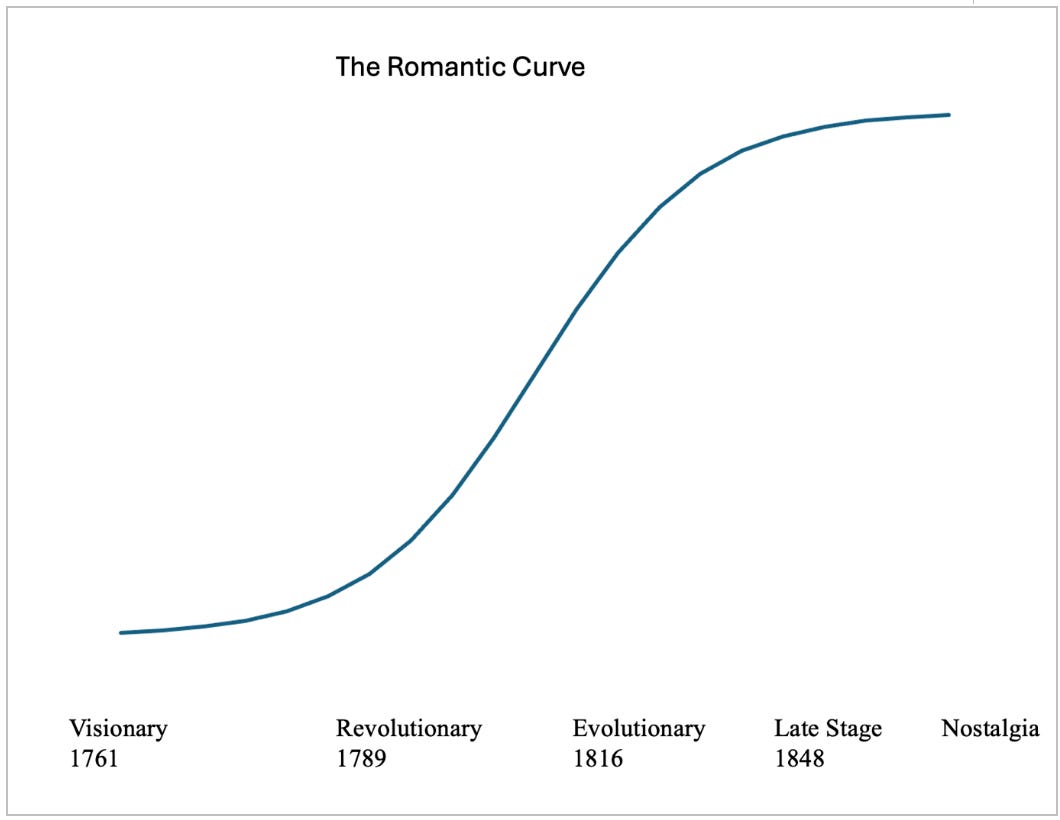

Visionary: the first stirrings of the romantic movement are most visible in literature, and we can see this in the novels of Rousseau and Goethe. Rousseau is more typically placed in the Enlightenment era but in this Cultural System, as an Enlightenment thinker, he was a minor opera composer but turned instead to literature and philosophy with 1761 Julie ou la nouvelle Héloïse and with philosophies Du contrat social published in 1762. This then can be the marker for when there was a visionary sense that emotion had to be at least equal to reason. Then more markers become apparent such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Die Leiden des jungen Werthers in 1774. But at the same time, there was a movement to enlist officers of talent rather than heredity. This to the point where two ranks were created one for the ennobled ranks and one for merely talent, and the most obvious example is Napoleon I who was promoted on talent starting with 1785. This meant that the American Revolution was in this Cultural Systems aspect, a visionary revolution that took from both the Enlightenment and the burgeoning Romantic Movement different ideas.

Revolutionary: the most obvious example of a moment that starts a revolution is of course the French Revolution of 1789 and the Constitutional process of 1788 in America. These states had a written constitution rather than an unwritten one. Because it set off a host of other revolutions, especially in the New World it was very clearly a revolutionary era on a global scale cementing the precursor era to what followed. This tension between the established order based on rank and “careers open talent” was the fault line of the romantic age. During the Revolutionary period France was the epicenter of the new idea that mankind, women were still at best second-class citizens if not third, was all equal in certain aspects. This idea had been known from 1776 in the Declaration of Independence from the United States but was put on firmer footing by the plebiscite ratified Constitution of 1793 in France and the Constitution of 1789 in America. These ratified the idea that certain rights adhered to all male citizens. But at the same time, a counter order was being promoted and that was that it was constitutional monarchy which should be the order of the day, centering itself in the United Kingdom and in Russia most particularly. The revolutionary era was the most intense of the periods in this Cultural System. That meant that in 1815 the decision was made in Europe to go down the road of the conservative movement rather than the liberal movement, but in the Americas, there was still attention between the two movements and many nations would shift between the two over the course of the next century.

Evolutionary: Because of the abrupt position of the Congress of Vienna of a new monarchy system, the evolutionary era started with a bang. This meant that the monarchs of Europe were established in the convention. In science the grounding of the calculus into the web of proof that had been the hallmark of Western mathematics in 1823. This meant that science was on a firmer footing and indeed the term scientist, promoted by William Whewell, replaced the older “natural philosopher” as the period wore on. This was also promoted by the architecture which was more solid, especially in the Beaux Art which began in the 1830s in Paris. The idea was to bolster the solidity of the government by having monuments to its very existence. The period can be thought of as two separate divisions: the Bourbon monarchy in France showed the conservative nature of the Congress of Vienna, but it was overthrown in 1830 with the Bourgeoisie taking a greater role in the state. Indeed, the monarch was termed “Roi des Français “that is he was king of the French rather than the King of France. But the industry was the whole towards a new form of commercial form of social organization with the idea that socialism be enacted to protect the most vulnerable. This too was a conflict that continued long after the romantic era had ended.

Late Stage - because the romantic was violent in its nature the revolutions of 1848 came almost as if by magic, because there were growing liberal and socialist movements in the continent of Europe and there was also the incorporation of the Americas into the polity of the old continent. Again, the broadening of a European ideal was essential for instantaneous communication. The sense that the Industrial Revolution required communication of the goods available and the detailed manufacture came to the forefront. This meant that a bottom-up rather than a top-down was necessary for the manufacturing of more complicated systems such as the rotary printing press to manufacture large volumes of print, the sewing machine to be able to rapidly innovate costumes, and a way of taking measurements by the manufacture of blueprints were all signature elements of a design process which was more complicated than before. However, the late stage of the Romantic era started rapidly and ended by 1852, when the Romantic President of France became the leader of the Second Empire.

Nostalgia: in a very real sense the Romantic era was both ignored and celebrated. The mechanisms of government and science were rapidly taken over by the neoclassical. But in music and in art in general, the shapes colors, and forms of the romantic movement were celebrated and codified, especially in the Salon of Paris. Indeed, the central role of Paris in both the Romantic and Neoclassical eras makes it so that the two periods are often thought of as the same, even though by markers they are completely different. Essentially the neoclassical era was a realm of dominant nation-states, industrial activity such as the telephone and the lightbulb, and the dominance of calculus as the way to describe the underpinnings of science. Thus Wagner, Brahms, and Mahler are described as “Romantic Composers” and even the Twelve-Tone Composers. Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern are described as the very last of the Romantics.

Thus endeth the lesson.

i Reid, Gordon McGregor. “Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778): His Life, Philosophy and Science and Its Relationship to Modern Biology and Medicine.” Taxon 58, no. 1 (2009): 18–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27756820, called Reid, 18.

ii Reid, 18.

iii Reid, 19.

iv Stearn, W. T. “The Background of Linnaeus’s Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology.” Systematic Zoology 8, no. 1 (1959): 4–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/2411603 called Stern, 5.

v There is a good summary of the Buffon- Linnaeus controversy in Sloan, Phillip R. “The Buffon-Linnaeus Controversy.” Isis 67, no. 3 (1976): 356–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/230679.

vi Feynman, Richard. 1972. Statistical Mechanics. Addison Wesley, Reading MA. 1.

vii Stearn, 4.

viii Strearn, 4.

ix Kant, Immanuel. 1912. Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics, Trans. Paul Carus, The Open Court Publishing Co. Chicago, IL.

x Grabiner, Judith V. “Who Gave You the Epsilon? Cauchy and the Origins of Rigorous Calculus.” The American Mathematical Monthly 90, no. 3 (1983): 185–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2975545. Called Grabiner . 193.

xi And most people know where this is by Grabiner’s pointing it out: Cauchy, Calculuss infinitesimal, Oeuvres, series 2, vol. 4, 122 which is 171-175 in the English translation. Grabiner, 194. This is one of the pinnacles of calculus because up until that point the calculus was not grounded.

xii It was the precursor of Cambridge’s mathematical rigor and the Romantic’s style of proof. Philip C Enros. 1983. “The Analytical Society (1812–1813): Precursor of the renewal of Cambridge mathematics”, Historia Mathematica, Volume 10, Issue 1, 24-47, ISSN 0315-0860, https://doi.org/10.1016/0315-0860(83)90031-9. 24.

xiii Blake, William. 1797. Quoted from https://blake.lib.asu.edu/html/the_four_zoas.html, Verse 360